The Lost Verses of Tin Pan Alley

How the classic songs of Tin Pan Alley lost their verses.

Guest article by LtCol Richard Beil, USMC(Ret), M.A.T.

Popular standards are, according to Webster, "something established as a rule or basis of comparison in measuring or judging quantity, quality, value; …a piece of music that has remained popular for many years;…”. This certainly describes the “standards” of Tin Pan Alley. The words and music reflect the creative personality of the songwriters and, many times, their personal recollections and emotions.

In the early years of Tin Pan Alley, these recollections and emotions were expressed through “stories” embedded in the songs. The song’s verse(s) set the stage or provided the background underlying the main idea which would be stated and repeated in the chorus. The verse, chorus, verse, chorus form of music, which was at the heart of early Tin Pan Alley songs, derived from the classical music tradition of the “strophic” form, a sectional way of structuring a piece of music based on the repetition of one formal section or block played repeatedly.

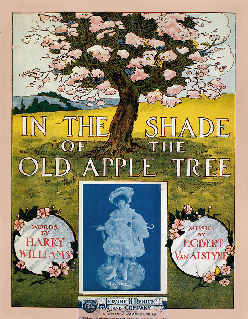

As time passed, however, the verse(s) fell into disuse for a variety of reasons. And, although the repetitive chorus is able to stand alone as a good tune, it takes the “story” provided in the verse to fully appreciate the song’s true meaning. In  the Shade of the Old Apple Tree was the first big hit of Egbert Van Alstyne. Written in 1905, it is a very recognizable standard. Most consider the line “With a heart that is true, I’ll be waiting for you, in the shade of the old apple tree” as simply a somewhat lighthearted promise akin to “I’ll meet you at the malt shop”.

the Shade of the Old Apple Tree was the first big hit of Egbert Van Alstyne. Written in 1905, it is a very recognizable standard. Most consider the line “With a heart that is true, I’ll be waiting for you, in the shade of the old apple tree” as simply a somewhat lighthearted promise akin to “I’ll meet you at the malt shop”.

However, once the 2nd verse is included, it becomes clear that the promise is much more meaningful. It completely changes our perception of the song:

I’ve really come a long way from the city

And, though my heart is breaking, I’ll be brave

I’ve brought this bunch of flow’rs, I think they’re pretty

To place upon a freshly molded grave

If you will show me, Father, where she’s lying

Or, if it’s far just point it out to me

Said he, “she told us all when she was dying to bury her beneath the apple tree”

In other cases, knowing the lyrics of the verse doesn’t necessarily change our perception. It simply expands the narrative and makes the chorus make more sense. Take the old favorite I Want a Girl (Just Like the Girl That Married Dear Old Dad), from 1911 with music by Harry Von Tilzer and lyrics by Will Dillon. Most everyone is familiar with the  chorus:

chorus:

I want a girl just like the girl that married dear old Dad

She was a pearl and the only girl that Daddy ever had

A good old fashioned girl with heart so true One who loves nobody else but you Oh, I want a girl just like the girl that married dear old Dad

The verse introduces the underlying story of a boy who has been searching, but in vain:

When I was a boy, my Mother often said to me

Get married boy and see, how happy you will be

I have looked all over but no girlie can I find

Who seems to be just like the little girl I have in mind

I will have to look around, until the right one I have found.

This article will endeavor to explain the various reasons the verse(s) were “lost”.

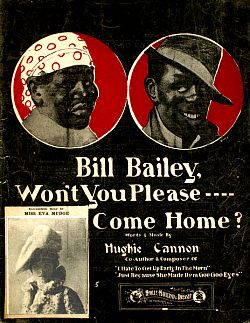

In some cases, either the melody or rhythm of the verse actually was at odds with the “feeling” or emotion transmitted by the chorus. Bill Bailey Won’t You Please Come Home (Hughie Cannon, 1902) is a good example of the “Cake Walk” style of music that predated Ragtime. In essence, a Cake Walk was a mildly syncopated march originated by slaves on southern plantations.

style of music that predated Ragtime. In essence, a Cake Walk was a mildly syncopated march originated by slaves on southern plantations.

"...the cake walk was originally a plantation dance, just a happy movement they did to the banjo music because they couldn't stand still. It was generally on Sundays, when there was little work, that the slaves both young and old would dress up in hand-me-down finery to do a high-kicking, prancing walk-around. They did a take-off on the manners of the white folks in the "big house", but their masters, who gathered around to watch the fun, missed the point. It's supposed to be that the custom of a prize started with the master giving a cake to the couple that did the proudest movement. [1].

So, the winning couple would "take the cake"."

The verse of “Bill Bailey” is in a minor key which doesn’t lend itself to “a high-kicking, prancing walk-around”. The tune and melody simply don’t “fit” the happy theme of the chorus. This is the most logical explanation for it’s falling into disuse.

Another factor which probably contributed to dropping the verse was songs that were written with different time signatures in the verse and chorus, making it difficult for people to dance. Wait ‘Til the Sun Shines Nellie (m. Harry Von Tilzer, w. Andrew Sterling, 1905) is a case in point. The verse is written in 4/4 time and is ballad-like. Then, the chorus switches to 2/4 time and is almost march tempo. How would a couple be able to dance to such a tune with the orchestra switching back and forth?

Another factor which probably contributed to dropping the verse was songs that were written with different time signatures in the verse and chorus, making it difficult for people to dance. Wait ‘Til the Sun Shines Nellie (m. Harry Von Tilzer, w. Andrew Sterling, 1905) is a case in point. The verse is written in 4/4 time and is ballad-like. Then, the chorus switches to 2/4 time and is almost march tempo. How would a couple be able to dance to such a tune with the orchestra switching back and forth?

However, the most significant factors contributing to verses becoming “lost” were the transition from Vaudeville to “Broadway” shows, the advent of broadcast radio, and the invention of electronic recording. In the latter part of the Tin Pan Alley era (late 1920s and later), the Tin Pan Alley style developed an even closer connection to the Broadway stage than had existed in the past. During this period, a number of factors combined to shift the form and strategies of the basic song-type. Technology and other considerations imposed stringent demands on the length of songs. Of these, recording was initially the most restrictive in its demands, but the new venue of broadcast radio also had a great influence. "The most basic change, however, involved the narrative and dramatic role of song. By this time, songs had moved away from the self-contained narratives they presented in the first decades of the era, to a type of song whose basic task was to articulate a moment within the greater narrative of a show."[2]

Acoustic and Electronic Recording

Before 1925, all recording was done acoustically: the artist performed into a recording horn or “megaphone”, and the sound waves imbedded a groove in the wax master disc. The playing time of a phonograph record depended on the turntable speed and the groove spacing. At the beginning of the 20th century, the early discs played for two minutes, the same as early cylinder records. The 12-inch disc, introduced by Victor in 1903, increased the playing time to three and a half minutes. 78 rpm was the standard recording speed...more or less. Some companies recorded at 76, 80, or even 82 rpm. Most phonographs had adjustable speed controls, so matching the playback speed to the recording speed wasn't a problem. The average record was 10 or 12 inches wide and made of shellac. Because a 10-inch 78-rpm record could hold about three minutes of sound per side and the 10-inch size was the standard size for popular music, almost all popular recordings were limited to around three minutes in length. This limitation on the length of both popular-music and jazz songs persisted from 1910 until the invention of the LP, in 1948.

Electronic recording was introduced in 1925. Now, instead of screaming into a recording horn, the artist performed into a microphone, and the recording was created by electrical wiring and amplifiers. This made an exact speed of 78 rpm an absolute necessity. The new technology gave us better sound quality, greater amplification, and made it possible to record large groups, such as full orchestras and choirs.

Radio

“The earliest surviving recordings of a radio signal are segments of Morse code transmissions recorded off the air in late 1913 or 1914 by Charles Apgar, a New Jersey radio amateur. Experimental recordings of radio programs were made by various phonograph companies and research laboratories almost from the beginning of broadcasting in the early twenties, using the newly-developed electrical recording process and producing phonograph-record pressings from wax masters.”[3]

Coincident with the strict recording time mentioned above were the “formats” that radio stations began using. To allow time for advertising, news, and other announcements, radio began placing restrictions on song length. By the end of the Tin Pan Alley era, the generally accepted rule was that a song should be no more than 3 ½ minutes in length. To ensure that recordings fit this format, the “radio edit” came into practice.

A radio edit is often just a shortened arrangement that makes a song conform to a particular structure. Some radio edits are just "early fades", the song not being played to completion. A professional radio edit may shorten the track by removing many short sections of the track, such as long guitar solos or instrumental sections rather than simply fading out at the end. Since it is usually shorter than the original version, a radio edit is more cost-effective for commercial radio stations, allowing more time for commercials, talk, news and other content to be programmed. Of course, as time passed, composers began writing to conform to the limits in order to have their songs played on the air.

The Narrative and Dramatic Role of Song

Although the Tin Pan Alley song-type continued to include verses, these most often were much shorter, sometimes serving as little more than introductions. The song became, in most cases and for most purposes, coextensive with the chorus. And, as was quickly learned within the time-restrictive environment of recording in the 1920s, the new Tin Pan Alley song, uprooted from the stage, worked best without its verses, as a fragment of expression that was somewhat fluid.

As this kind of fluidity became the ideal, a specific narrative within the song was not only beside the point, but also a potential source of interference. When the song was performed separately from the greater narrative of the stage play, the verse (especially if it was of any length) became a curiosity. It tended to detract from the emotional immediacy of the song itself, as depicted in the chorus. Were the verse to be included in a non-stage setting, it would often be sung after the chorus, thus allowing the chorus to make the first and most important connection with the audience.

An example of the change to short “intro” verses is Irving Berlin’s White Christmas. Berlin wrote the song while sitting poolside in 1940 at the Arizona Biltmore Hotel and Spa in Phoenix. The original verse tells of a Los Angelino who, amid orange groves and palm trees, longs for a traditional Christmas “up north”.

The sun is shining, the grass is green. The orange and palm trees sway

There’s never been such a day. In Beverly Hills, LA

But, it’s December the 24th. And I am longing to be up north.

The song was introduced in the 1942 movie Holiday Inn, which starred Bing Crosby and Fred Astaire. Berlin, himself, removed the verse from the song and very few have ever heard it.

The designation “thirty-two bar song form” has been used to describe the standard form of the later Tin Pan Alley song’s chorus. However, composers exercised a great deal of flexibility in how they filled those 32 bars. More important to the song form than its precise length was the repetition of key phrases, which would both “sell” the song commercially and establish a central, emotional “truth” for the song. This came to be termed the “hook”, which often was simply the sung title of the song. This “hook” served both expressively and as a built in “jingle” through which the song advertised itself.[5]

An example of this “hook” or “jingle” that made a song memorable without the verse is Cuddle Up a Little Closer, Lovey Mine (m. Karl Hoschna, w. Otto Harbach, 1908). As in the case of I Want a Girl, we don’t need the verse, but it sure is nice to have it:

An example of this “hook” or “jingle” that made a song memorable without the verse is Cuddle Up a Little Closer, Lovey Mine (m. Karl Hoschna, w. Otto Harbach, 1908). As in the case of I Want a Girl, we don’t need the verse, but it sure is nice to have it:

On the Summer shore,

Where the breakers roar,

Lovers sat on the glistning sand.

And they talked of love,

While the moon above,

And the stars seemed to understand.

Then she grew more cold,

And he grew more bold,

'Till she tho't that he had better go.

But altho' he heard,

He not even stirred Only murmured in tones soft and low.

When you listen to this song (click on the cover image at left) you may be surprised. The verse melody is so different from the chorus, it is as though it belongs to some other song. This is also another example of the difficulty of dancing to a verse and then a completely different chorus.

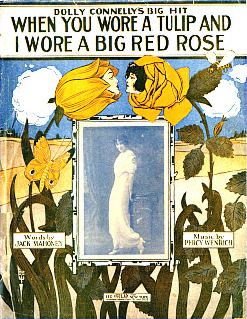

I want to end the musical examples with a song that is very special to me. Early on in my life, I learned the greatness of the Tin Pan Alley songs from my great uncle and grandfather. My great uncle had been born in Canada in 1877 and learned to play the cello. When he came to the U.S. around the turn of the century, he settled in New York City, where he obtained work playing in the "pit" orchestras of the burlesque and vaudeville theaters. He knew such people as George M. Cohan, Al Jolson, and Faye Templeton personally and would tell me such wonderful stories about those times. But from my grandfather, I learned my favorite example of this "hook" or "jingle" that made a song memorable without the verse, When You Wore a Tulip (And I Wore a Big  Red Rose) (m. Percy Weinrich, w. Jack Mahoney, 1914). This song has very special meaning for me. As a boy, I would ride with my grandfather and listen to him sing this at the top of his lungs. He was born in 1910, so he probably knew that the song had a verse, but he only ever sang the chorus. Other than children's songs, I think it's the first song I ever learned. Again, we have a verse rarely if ever heard after the roaring twenties:

Red Rose) (m. Percy Weinrich, w. Jack Mahoney, 1914). This song has very special meaning for me. As a boy, I would ride with my grandfather and listen to him sing this at the top of his lungs. He was born in 1910, so he probably knew that the song had a verse, but he only ever sang the chorus. Other than children's songs, I think it's the first song I ever learned. Again, we have a verse rarely if ever heard after the roaring twenties:

I met you in a garden in an old Kentucky town,

The sun was shining down, you wore a gingham gown;

I kissed you, as I placed a yellow tulip in your hair,

Upon my coat you pinned a rose so rare.

Time has not changed your lovliness, you're just as sweet to me,

I love you yet,

I can't forget the days that used to be.

So, we see that there were multiple factors, working over the course of many years, that resulted in people born in the late 1920s and early 1930s growing up hearing the “standards” without ever knowing there was any more to the song than the chorus.

"And thus, we live in the twilight of the Tin Pan Alley era. It's not popular culture, in the sense that it's so rarely "top forty" material, yet it's still around."[6] Tragically, we will never again see the likes of this wonderful style of songwriting. But, we can preserve this rich and important history by passing it along to new generations, introducing them to the music of Tin Pan Alley.

Richard G. Beil, January, 2009

In keeping with Parlorsongs’ mission of preserving this musical heritage, and to make our own small contribution to music’s historical record, we have just released a new CD entitled “The Lost Verses: Songs You Thought You Knew”. It is the first ParlorSongs offering that includes a vocal track and we have taken great care to bring you the songs in their entirety. The author of this article (Rich Beil) has provided his great talent to sing these great old songs for the CD production.

In keeping with Parlorsongs’ mission of preserving this musical heritage, and to make our own small contribution to music’s historical record, we have just released a new CD entitled “The Lost Verses: Songs You Thought You Knew”. It is the first ParlorSongs offering that includes a vocal track and we have taken great care to bring you the songs in their entirety. The author of this article (Rich Beil) has provided his great talent to sing these great old songs for the CD production.

While copies of old vocal recordings are available, they are still copies of songs done in the days of singing into a megaphone. Even with filtering and digital enhancement, the result is still a recording with very limited and compressed sonic range and unclear instrumentation. And, many of the vocal renditions are just lost forever.

In developing the idea for this CD, Rich thought that many Parlorsongs visitors might like to hear the songs done using modern equipment. If you take a moment to visit the Parlor Store, you’ll see that we have included many of the standards that you’ll recognize. We’ve also added some songs that many will have never heard. We hope you find them both educational and entertaining. We believe that this CD would make a great, inexpensive gift for an elderly loved one, to bring them moments of joy and fond memories of days gone by. Or, you may want your own copy to share this rich musical heritage with your own children and grandchildren. Proceeds from the sale of this CD help us at Parlor Songs defray expenses and continue to bring you America's songs from Tin Pan Alley.

If you'd like to buy the CD now, for US addresses, you can do so via PayPal using your Mastercard, Visa or Discover card using this link:

For overseas orders, please contact us for additional shipping costs.

For those of you who would prefer MP3 versions, the price is $14.95 for anywhere in the world or beyond if you are from another planet and have a good internet connection. Download of the complete set of CD tracks should take approximately 57 minutes with a broadband connection.

Finally, we are in the planning stages of our next project. Because many first-time visitors to Parlorsongs find our site while searching for information about Irving Berlin, we hope to be able to bring you a compilation some of his pre-1923, public domain works if this first vocal CD proves to be popular. Our working title is Early Berlin-Songs of a Young Master and as a work in progress we expect it to include at least 25 of his songs and may be a double CD set. Some will be his early hits like Alexander’s Ragtime Band. But, there will be others that many will have never heard, like Crinoline Days and He’s a Rag Picker.

Footnotes:

[1] Baldwin, B. (1981). The Cakewalk: A study in stereotype and reality. Journal of Social History, 15 (2), 208.

[2] The American Musical and the Formation of National Identity by Raymond Knapp, 2005, page 77

[3] Documenting Early Radio: A Review of Existing Pre-1932 Radio Recordings by Elizabeth McLeod, 1998

[4] op cit, page 78

[5] ibid

[6] Why Tin Pan Alley Matters by Dr. Michael Garber, PhD, 2008

If you are new to us, to enjoy the full musical experience, we

recommend that you get the Scorch plug in from our friends at Sibelius software.

The Scorch player allows you to not only listen to the music but to view the

sheet music as the music plays and see the lyrics as well. Each month we also

allow printing of some of the sheet music featured so for those of you who play

the piano (or other instruments) you'll be able to play the music yourself.

It's a complete musical experience! Get the Sibelius

Scorch player now. ![]()

Richard Beil, January, 2009. This article published January, 2009 and is Copyright © 2009 by Richard Beil and The Parlor Songs Association, Inc. Text, images or music may not be reproduced in part or in total without express written permission of the author or a company officer. Though the songs published on this site are often in the Public Domain, MIDI renditions are protected by copyright as recorded performances.

Thanks for visiting us and be sure to come back often to see our new features or to read some or all of our over 130 articles about America's music. See our resources page for a complete bibliography of our own library resources used to research this and other articles in our series.

If you'd like to contribute an article to us at Parlor Songs, we'd love to have your help and contribution. The "rules" for submissions can be found here, we'd love to have submissions by any of our readers, anytime and would enjoy having a "reader submission" or "favorites" feature from time to time. Heck, get involved, help us out and write a feature for us!

Parlor Songs is an educational website about American popular music and the history of the genre

If you would like to submit an article about America's music for publish on the website, contact the email on the main page. I also welcome suggestions for subjects for future articles.

![]()

All articles are written by the previous owners, unless otherwise stated.

©

1997-2024 by Parlor Songs (former owners Richard A. Reublin or Richard G. Beil). Before using any of these images, text or performances (MIDI or other recordings), please read our usage policy for standard permissions and those requiring special attention. Thanks.

I respect your privacy and do not collect or divulge personal information.